This section includes snippets of history and our current context. It is in no way comprehensive of what is known, and there is sure to be far more still unknown to us

History of Third-Gender People Worldwide

The gender binary is a relatively new, and very colonial, way of understanding gender, as is the term transgender. People have existed outside of a strict, two-gender system as far back as humans have uncovered thus far. Here are just a few examples:

- Europe during antique, medieval, and early modern times (LaFluer, Raskolnikov, & Kłosowska, 2021)

- Africa in pre-colonial times, including the mudoko dako in Uganda, the Mwami in Xambia, the okule and agule of Lugbara, and the chibados in Angola. In these societies, those who embodied a mix of masculine and feminine characteristics and roles were understood to be highly spiritual beings, coming from the divine. Records from the Portuguese Inquisition describe some of this through their own lens, though they brought with them transphobia and violence to those who transgressed their European views of gender. (Elnaiem, 2021; Roxburgh, 2022)

- Phillipines during pre-colonial and early colonial times, called baylans or asogs, and later baklâ, also held spiritual roles within their communities, serving as shamans or as a bridge between the physical and spiritual realms (Rodriguez Alegre, 2022). Here, sex and gender were viewed as both biological and psychological. When the Spanish conquered, they forced Roman Catholicism on its people (Chan, u.d.). Today, transpinays and transpinoys face much discrimination and violence (United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, 2012).

- India’s third gender has been referenced throughout ancient Hindu law, medicine, and astrology (Michelraj, 2015). They were once highly regarded in society, then faced much discrimination and criminalization for a long time post-colonization. Today, the hijra have gained some crucial legal recognition back.

- Samoa recognizes four genders – man, woman, fa’afafine, and fa’afatama. The latter two take on the roles of elder caretakers, village greeters, and sex educators (National History Museum, 2020a).

- The Machi people in Mapuche, Chile were also revered as highly spiritual, able to ebb and flow between genders, bringing balance to their world (National History Museum, 2020b).

- The Muxe, who live on the Istmo de Tehuantepec in Oaxaca, México, continue to be celebrated within their small community, as they have been since pre-colonial times (Kaur, 2023; Synowiec, 2018). The Zapotec people, similar to other indigenous cultures with third genders, viewed gender more as cultural, social, and spiritual, rather than sexual. The muxes rarely consider themselves to be women, nor do they consider themselves gay. Muxe is a distinct identity, one that hopefully will continue to be celebrated and revered for centuries to come.

In all of these cases, colonialism brought transphobia and violence to the indigenous people of those lands, and now third gender people experience much violence and discrimination across the globe.

History of Two Spirit and Trans People in the United States

Indigenous people of Turtle Island (now called North America) highly respected and revered those were third gender. Individual nations had – and continue to have – their own terms to describe third gender people within their tribal nation, such as the Nádleeh/Nádleehi of the Diné (Navajo) people, the wíŋkte of the Lakota people, and the Ihamana of the Zuni people. The word “Two Spirit” was coined by Myra Laramee (Cree) in 1990 to have intertribal language for “another gender role believed to be common among most, if not all, first peoples of Turtle Island (North America)” (Montiel, 2021; Two Spirit Society of Denver, 2011). Like other indigenous cultures worldwide, Two Spirit people held a highly spiritual role in society as shamans, embodying both masculine and feminine energies. And, like other cultures around the world, colonizers brought with them their binary understanding of gender, and Two Spirit people in the United States now face much discrimination.

There is documentation that trans people in the US were criminalized as far back as the mid-19th century when it was illegal to wear clothing not in accordance with one’s sex. The mid 1900s saw many police raids on gay bars and the criminalization of sex work, which many trans femmes – largely Black and Brown – engaged in because of discrimination in employment and housing based in transphobia and racism. These trans femmes, known as “street queens”, then become even more vulnerable to violence and health hazards. The criminalization of sex workers went as far as police profiling and arresting trans femmes under a biased assumption that they might engage in sex work. For survival, Black and Brown trans women began forming Houses, chosen family who took care of each other and mentored each other. Drag balls also started around this time, which was a way to celebrate and support the trans femmes (and some trans men) most marginalized by society.

Resistance

- Cooper’s Do-Nut (Los Angeles) – street queens, male hustlers, and those with them – police presence – would ask for IDs. Their names, genders, presentation would not match and they would be arrested for prostitution, loiering, or other “nuisnace crimes”. May 1959, police busted in, queens resisted. Threw donuts, fighting in the streets. In the end, even those initially arrested managed to escape.

- Dewey’s (Philadelphia) – always been a place where queer and trans folks frequented. April 25, 1965, they were refused service. Protests, sit-ins, and informational pickets ensued, and in May 1965, Dewey’s backed down on their discriminatory practice.

- Compton Cafeteria (San Francisco) – August 1966 – similar to Cooper’s Do-Nut, where largely Black and Latinx street queens, male hustlers, other queer and trans youth frequented throughout the night, police were called in to remove a group of loud youth. When the police grabbed one queen, she threw coffee in his face. Food, plates, trays, and table were thrown and overturned, glass was broken, fighting spilled into the streets as police called for backup.

- Stonewall (New York City) – June 28, 1969 – Stonewall Inn in New York’s Greenwich Village – as police again raided the bar, people began resisting. A transmasculine person resisted arrest, and Sylvia Rivera threw a beer bottle at an officer. Bottles and rocks were thrown at police, and police beat patrons. Thousands of people came out from the neighborhood, and police barricaded themselves in the bar and called for backup. Protests lasted for a couple of days before dissipating.

Trans Exclusionary Activism

- 1950s through 1970s, that gay and lesbian people started separating themselves from transgender people in politics and advocacy. For example, “homosexuality” was removed from the DSM in 1973, and “Gender Identity Disorder” was added in the next edition in 1980. It remains in the DSM today as “Gender Dysphoria”.

- Second wave feminism of the 1970s became about white, middle-class, heterosexual, cis women, worried that including women of color and queer women would detract from gaining rights for white women. In response, the National Black Feminist Organization of New York City and the Combahee River Collective of Boston formed that recognized intersectionality and the interconnectedness of various struggles.

- 1972 San Francisco Pride include drag performers, so a group of gays and lesbians against trans people and the “mockery” of women started a separate pride celebration the following year. The original Pride never again happened, and the anti-drag one is what is now SF Pride.

- In New York, organizers tried to stop Sylvia Rivera from speaking at the Christopher Street Liberation Day, but she took the stage anyway and spoke about the disenfranchisement of trans people and queer people of color in the “mainstream” gay liberation movements of that time.

- Lesbian separatist groups began forming, saying that all trans women were an “unwanted penetration” into women’s space, violating them.

1990 – Current

- Around 1990, “transgender” became the umbrella term for those with non-normative genders

- HIV/AIDS crisis, gays and lesbians realized that trans people were also impacted and that they had to align forces in a larger “queer” movement, reclaiming that word.

- Early to mid 1990s, organizations grappled to add the “T” to the acronym and include trans people in their organizations and advocacy efforts. This again “whitewashed” the work, focused instead on white, middle class LGBT people and not the radical work of queer movements based in alliance and resistance. Sometimes the “T” was added just to be politically correct, other times “transgender” became confused with sexual orientations.

- Due to work of trans activists, transgender anti-discrimination ordinances started to be passed in the mid-1990s.

- Early 2000s: Increased media about and by transgender people through books and films

- Increased advocacy by, and legislation for, lesbian, gay, and bisexual people often left out trans people. The leading organization, Human Rights Campaign, intentionally left trans people out of its lobbying for the Employment Non-Discrimination Act at first (first introduced in 1970s, didn’t make it to Congress until 1994 when it failed by 1 vote. The HRC lobbied for trans inclusion in ENDA in 2007, but a gay man congressman split it into two bills – one for sexual orientation, one for gender. The HRC endorsed the split bills. The sexual orientation one passed; the gender did not, but neither made it to the Senate.

- 2011: the first large trans discrimination survey, “Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey”

- 2016: Even larger “Report on the 2015 National Transgender Survey”

- 2016: Oregon legalizes a “nonbinary” gender option

- 2016: Many Republican campaigns had anti-trans legislation as a core campaign promise

Stryker, S. (2017). Transgender history: The roots of today’s revolution. New York, NY: Seal Press.

- 2023: Anti-trans legislation continues to rise, with 615 anti-trans bills introduced in the United States that year, 53 of which were at the federal level. Of the 615 bills, 188 targeted healthcare, 172 education, 153 other, 73 sports and 29 bathrooms (Trans Legislation Tracker, 2024).

- 2024: Anti-trans legislation rises further, with 652 bills on the table as of 9/10/2024, 79 at the national level. Bills targeting education have now taken the lead with 197 bills, followed by other (192), healthcare (174), sports (61), and bathrooms (28) (Trans Legislation Tracker, 2024).

History of Transgender Support in Higher Education

Between the 1950s and 1970s, universities like UCLA and the University of California conducted early research on trans people, and Johns Hopkins University opened the first medical program for gender-affirming hormones and surgery.

1971: Colleges mirrored national movements, starting with gay and lesbian groups. The Gay People’s Union was founded at the University of Wisconsin, Madison and The University of Michigan established the first campus center, called the Spectrum Center. This was due to advocacy by their two student groups, the Gay Liberation Front and the Radical Lesbians.

1991: First use of “queer studies” by Tersa de Lauretis at UC Santa Cruz. An anthropologist, Gayle Rubin, suggested “sexuality studies” instead, placing trans people in the realm of sexuality and eroticism rather than an internal sense of one’s own gender.

1990: Judith Butler wrote about “gender performativity” and that all gender expressions are performed as a way to be understood and to understand oneself, and thus that all genders are valid.

- In 2011, Butler wrote about how “biological sex” is also socially constructed.

1994: Iowa Queer Studies Conference

1995: first International Conference on Cross-Dressing, Sex, and Gender at Cal State Northridge

1998: Chronicle of Higher Education published an article about the emerging field of transgender studies

As more trans people came out, sex-specific schools needed to re-think their admissions policies. Many of them continue to grapple with this.

2003: Genny Beemyn, writing under their name pre-transition, wrote recommendations for universities to implement to better support transgender college students, including campus centers with paid staff, chosen name and gender update processes, all gender restrooms (mapped out), non-discrimination policies inclusive of gender identity and expression, trainings for employees, trans-specific groups and programming, and trans inclusive language on all materials and documents. Many of these things we are only beginning to implement at community colleges. (Beemyn, 2003)

2016: US Department of Education provided “significant guidance” that Title IX protections “on the basis of sex” includes transgender students

2017: One of the first acts of the Trump Administration, the US Department of Education rescinded the guidance provided in the 2016 Dear Colleague Letter on Transgender Students.

2021: US Department of Education confirmed that Title IX prohibits discrimination based on gender identity in all programs and activities at educational institutions that receive federal funding.

2024: US Department of Education dictate that schools receiving federal funding must prohibit discrimination on the basis of sex, and that this includes gender identity, sex stereotypes, and sex characteristics

As of 2011:

- Of the more than 400 colleges and universities known to have ‘‘gender identity and expression’’ in their nondiscrimination policies, only 22 are community colleges, and most of these are part of the University of Hawai’i and the City University of New York, which amended their nondiscrimination policies system-wide. As more universities implemented chosen name and gender policies, community colleges did not.

- Out of the 1,167 community colleges in the United States (American Association of Community Colleges, 2011), only the Community College of Denver had a professionally staffed LGBT center, and its director position was split with the University of Colorado at Denver and Metropolitan State College. In contrast, 170 LGBT centers with at least a half-time director position have been established at four-year U.S. institutions.

History of the California Community Colleges

- 1907: The Upward Extension Law made it possible for the creation of “junior colleges”

- 1910: The Collegiate Department of Fresno High School was established, which is now Fresno City College. This was the third public junior college in the US.

- 1930: 34 junior colleges with 15,000 students, more than 33% of the country’s community college student population.

- 1947: 55 junior colleges in California with over 60,000 students

- 1967: SB 669 established the Board of Governors of the California Community Colleges and the State Chancellor’s Office

- 1975: SB 160 opened up the possibility of collective bargaining units in K-12 and community colleges.

- 1988: AB 1725, the California Community College Reform Act, passed,which formerly designated the California Community Colleges and laid out guidelines for its operations

- 1988: Prop 98 provided a minimum funding guarantee for K-12 and community colleges.

- 1996: Prop 209 passed, which amended the CA Constitution to prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, sex, and ethnicity in public institutions

- 2001: AB 540 passed, allowing undocumented students who have lived and studied in California to receive in-state tuition

- 2015: SB 850 allowed 15 community college districts to establish one bachelor’s degree program

- 2017: Guided Pathways and the Vision for Success adopted among the CCCs as a framework and blueprint for reducing equity gaps and increasing student success

- 2018: Student-Centered Funding Formula adopted, financially incentivizing California Community Colleges to reduce equity gaps and increase student success metrics

- 2023: Vision 2030 announced, the next iteration of the Vision for Success, focused on Equity in Success, Equity in Access, and Equity in Support

- 2023: There were over 4,500,000 community college students in the United States during Fall 2023, 33% of whom were enrolled in the California Community Colleges

History of LGBTQIA2+ Support at the California Community Colleges

- 1972: City College of San Francisco held one of the gay literature courses in the United States

- 1989: City College of San Francisco established the first Gay and Lesbian Studies Department in the United States.

- 2005: City College of San Francisco established the Queer Resource Center, run by volunteers and students

- 2012: The Student Senate for CCC hosts the first conference of the Spectrum Caucus at San Francisco City College in May.

- 2013: CCC Apply added optional questions on sexual orientation and gender identity for applicants over age 18

- 2016: Mt. San Antonio College, San Joaquin Delta College, and Sierra College hire professional staff to provide LGBTQ+ resources.

- 2017: The Academic Senate for California Community Colleges established the LGBTQIA+ Caucus.

- 2017: The first CCC LGBTQ+ Summit was held at UC Riverside, with 330 participants. This Summit helped students, faculty, administrators, and other key stakeholders to develop relationships throughout the CCCs, share information that has aided in each individual campus’ work, and develop strength in numbers for statewide advocacy efforts. Subsequent Summits have been held in 2019 at UCR, and online annually starting in 2021. There are plans to continue and grow the Summit.

- 2019 : The CCC-LGBTQ-COMMUNITY listserv was established. This allowed regular communication across the state throughout the year.

- 2021: The 2021-2022 California state budget included the first $10 million allocation to the CCCs to better support queer and trans students.

- 2022: In addition to the CCC LGBTQ+ Summit, in person regional meetings were organized throughout the state.

- 2023: The 2023-2024 California state budget included a second $10 million allocation to the CCCs to better support queer and trans students.

- 2024: The 2024-2025 California state budget included a third $10 million allocation to the CCCs to better support queer and trans students.

Where We Are Now

The California Community Colleges received state funding pretty quickly after colleges came together and identified the need for LGBTQIA2+ student support. Practically, each college received $25,000-$50,000 per year on average, depending on the school’s population size and average student income. That amount of funding is not enough for full-time, permanent staff, and so funds are best used toward start-up and programmatic costs as colleges’ advocate for institutional funding by the time the state funding sunsets after 5 years.

Only five campuses currently have part- or full-time employees dedicated to LGBTQIA2+ student support, so most of this work is done by employees outside of their job description who are willing to volunteer their time (E, personal communication, September 21, 2023; JP, personal communication, October 20, 2023; LGBTQ+ @ California’s Community Colleges, 2024).

It is very difficult to have accurate representation of the trans and non-binary student population and to confidently disaggregate data to determine any equity gaps that exist.

- Data regarding students’ gender (and sexual orientation) is collected less often than any other demographic in all areas, including CCCApply, student information systems, HR systems for employees, interviews, focus groups, sign-in sheets, event registration, and other data collection methods (McFadzen et al., 2024).

- Only students age 18 years of age and older are able to answer questions related to gender (and sexual orientation) on CCC Apply, and the options are limited to male, female, non-binary, and decline to state, with a second question that asks whether or not students identify as transgender (McFadzen et al., 2024).The SOGI Coalition is advocating for expanded options, and brought this to the attention of the CCC Reimagine Apply Task Force in June 2024.

- Only data from the first gender question is released through CCCCO DataMart.

- When colleges do ask about gender, the majority of the time they limit to response options to align with CCC Apply (male, female, non-binary, decline to state; transgender: yes or no) or the U.S. Census Pulse Survey (male, female, transgender, none) (McFadzen et al., 2024).

- Only 21% of CCCs attempt to expand response options, and only 8% allow for self-identification (McFadzen et al., 2024).

- Only 24% of the colleges that gather data regarding students’ sexual orientation and gender reported using it to inform the college’s equity planning and work, or to connect students to resources. 61% of CCCs listed student privacy concerns as the main reason their access to data was limited (McFadzen et al., 2024).

Thus, colleges are trying to spend down one-time resource allocations quickly and meaningfully, without the time or staff to conduct a thorough needs assessment and strategically plan long-term, and using volunteers who want to assist but may not know where to start or how to coordinate the logistics. Thus, there is a sense of “flying the plane while building it”, putting institutional supports in place quickly without a foundation of knowledge and institutional infrastructure (E, personal communication, September 21, 2023; JP, personal communication, October 20, 2023; Tyler, personal communication, October 16, 2023).

This is where the Toolkit comes into play, to provide the needed foundation and blueprint for moving forward.

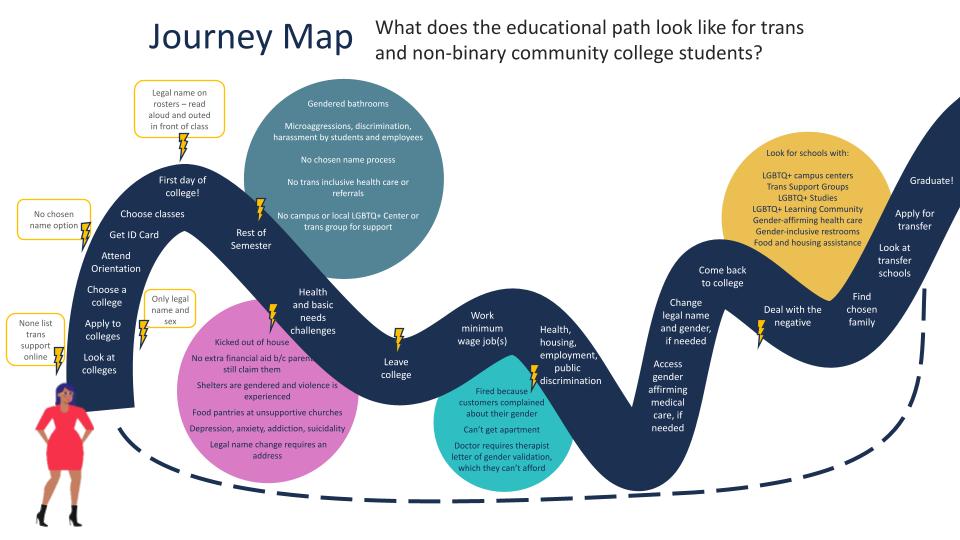

This next section gives some context into the experiences and needs of trans and non-binary community college students. While there is little data specifically about them (McFadzen et al., 2024), research on trans and non-binary bachelors-level students and research on community college students from other intersecting marginalized communities highlights that there are significant factors that impact students’ success. These factors and experiences take valuable time, energy, and effort away from coursework, which may contribute to lower persistence and retention rates. For students to succeed in the classroom, they must have access to the basic necessities for survival, have appropriate academic support, and have stability in their mental wellness, financial wellness, environmental wellness, and familial wellness.

General Statistics

45.4% of students that started at a US public community college in 2016 had not received a degree and were no longer enrolled after six years (National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, 2022).

Large equity gaps continue to exist among Black, Latinx, and Native American students in comparison with White and Asian students, whose six-year completion rates were 31.1%, 37.9%, 38.8%, 50.6%, and 53.4%, respectively.

Community college students are more likely to be non-traditional age, first generation, low-income, BIPOC, student parents, undocumented students, current or former foster youth, attending school part-time, commuting, and working more hours (Beer, n.d.; Okpych, 2022; PPIC Higher Education Center, 2017; Sockin, 2021).

The California Community Colleges have a greater population of undocumented students than the California State Universities and Universities of California combined.

While there is not accurate data regarding the total population of transgender students, about 70% of non-binary students at the CCCs are students of color (CCCCO DataMart, 2023).

General Information on Trans Students’ Academic Success

- 25% of trans people in the United States have a college degree, including associates, bachelors, and/or graduate degrees. An additional 26% have completed some college, and 48% have not attended college (James et al., 2024).

Some research shows that trans people have higher levels of formal education but lower earning potential than their cisgender counterparts (Grant et al. 2011; James et al. 2016), while others show that trans people have both lower rates of college completion and lower income (Downing & Przedworski, 2018; Meyer et al., 2017). A deeper look reveals that trans and non-binary students tend to leave college prior to completion, only to return years later to finish. Trans students consider leaving college at nearly twice the rate of cisgender students (37.8% vs. 17.9%) (Greathouse et al., 2018). This can put them at a substantial delay in their earning potential over their lifetime. There are many factors that seem to be at play in the consideration and decision to leave college prior to completion.

Negative Campus Climate

53% of trans people nationally reported being verbally harassed or disrespected in public spaces, and 22% reported being harassed by police (Grant et al., 2011).

Trans and non-binary college students:

- felt campuses were less welcoming and safe than their cisgender peers, reported a lower sense of safety and belonging, and perceived their campus environments as more negative overall (Dugan et al., 2012; Greathouse et al., 2018)

- faced additional difficulties within the educational environment itself, including poor treatment by peers, faculty, and staff (Grant et al., 2011; Nicolazzo, 2016)

The prevalence of the gender binary on college campuses, including restrooms and campus forms, along with a lack of a comprehensive name change process, negatively impacted trans and non-binary students’ mental health and the academic performance (Woodford et al., 2017).

What does this look like for trans and non-binary community college students in real life?

Promising (Related) Practices

Check these out for general promising practices!

What is already happening in higher education to support marginalized students?

| Support for Community College Students from Other Marginalized Communities | Support for Trans and Non-Binary College Students at Bachelors Conferring Institutions | |

| What Has Worked? | Learning experience: student success courses and supplemental instruction Sense of belonging: campus centers and peer mentorship programs Financial and basic needs: food, housing, health care, transportation, emergency funds, and job opportunities Academic counseling (Price et al., 2021) | Campus centers, learning communities, gender inclusive restrooms and housing, chosen name and pronoun processes, trans-inclusive health care on campus, non-discrimination policies, and trainings on trans-affirming practices (Catalano & Christiaens, 2022; Garvey, 2020; Goldberg et al., 2019). |

| Why Does It Work? | Help reduce equity gaps for Black and Latinx students in credits earned and rates of persistence, retention, graduation, and transfer (Baugus, 2020; California Community Colleges & Institutional Effectiveness Partnership Initiative, 2019; Kimbark et al., 2017; Parlier et al., 2022; Rima et al., 2018; Weiss et al., 2019) | Have worked to better support trans and non- binary students for the last 53+ years (University of Michigan, 2024). As that work has grown, they have been able to utilize trial and error, share best practices, make evidence-based changes, etc. |

| What’s Missing? | Fail to address the unique needs and experiences of trans and non-binary students, including a disproportionate lack of familial support, inequitable restrooms and health care, incorrect name and pronouns usage, and ignorant faculty. | Campus centers often cater to white, cisgender, queer people (Coleman et al., 2020; Darling-Hammond, 2023; Magpantay, 2020; Siegel, 2019). Queer and trans students of color at one university described their campus LGBTQ Center as white queer people talking about white queer topics, enacting racial microaggressions, and sometimes co-opting cultural practices of various BIPOC communities (McCoy, 2018). Students at four-year colleges are often traditional age (18-22) with most of their activities and basic needs provided on campus. Demographics also differ at community colleges, as referenced in “General Statistics” section above. |

The Time Is Now!

Community colleges have a responsibility to create something truly innovative, intersectional, and collaborative to truly eliminate barriers to trans and non-binary community college students’ academic success and increase rates of persistence, retention, graduation, and transfer.